An earlier study on which I worked took advantage of a disturbance on the east side of Mount Washington to study how quickly the alpine plant community would recover afterwards. We know from earlier research that these communities take a long time to grow back and that some species take longer than others to return. There is some evidence that mosses and lichens might be particularly vulnerable to disturbance so we wanted to include them in our surveys in addition to the vascular plants that dominate alpine communities. A trench was dug along the Cog Railway track in 2008 in order to bury a new electric line and photo-optic cable. The excavator that dug the trench eliminated plants in an area about 5 m wide all the way to the summit. David Taylor, a professor at the University of Portland in Oregon, and I surveyed plants in the disturbed area four years after the work was finished. We compared the plants in the disturbed area with plants just outside the area that was disturbed to see how closely they resembled each other, and we did this from the summit to several hundred feet below tree line.

We found that recovery had barely begun, four years after the disturbance. Only five flowering plant species had established in the disturbed area above tree line, compared with 15 in the undisturbed area, and many of our survey plots in the disturbed area still had no plants at all. Diversity and abundance of mosses and lichens were lower in the disturbed area as well. Previous studies have shown that, even where alpine plants recolonize soon after a disturbance, vascular plant abundance can remain low for decades to centuries. The rate of recovery appears to depend primarily on the severity and duration of the disturbance.

We hope to go back in a few years to see how the recovery is progressing. The report on our survey can be read here:

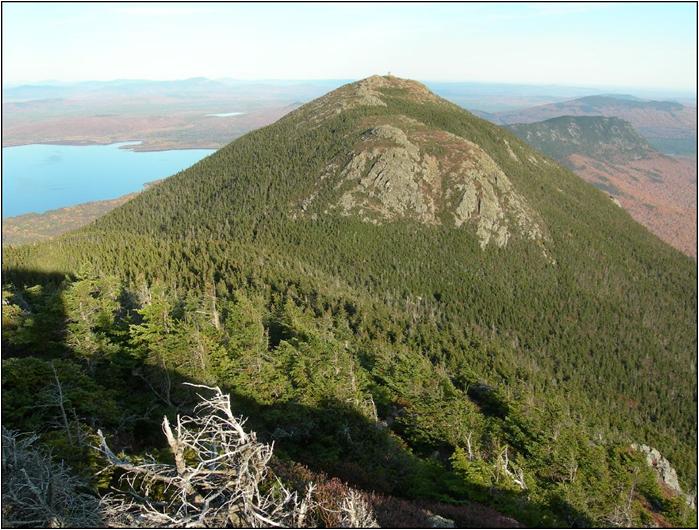

Mount Bigelow